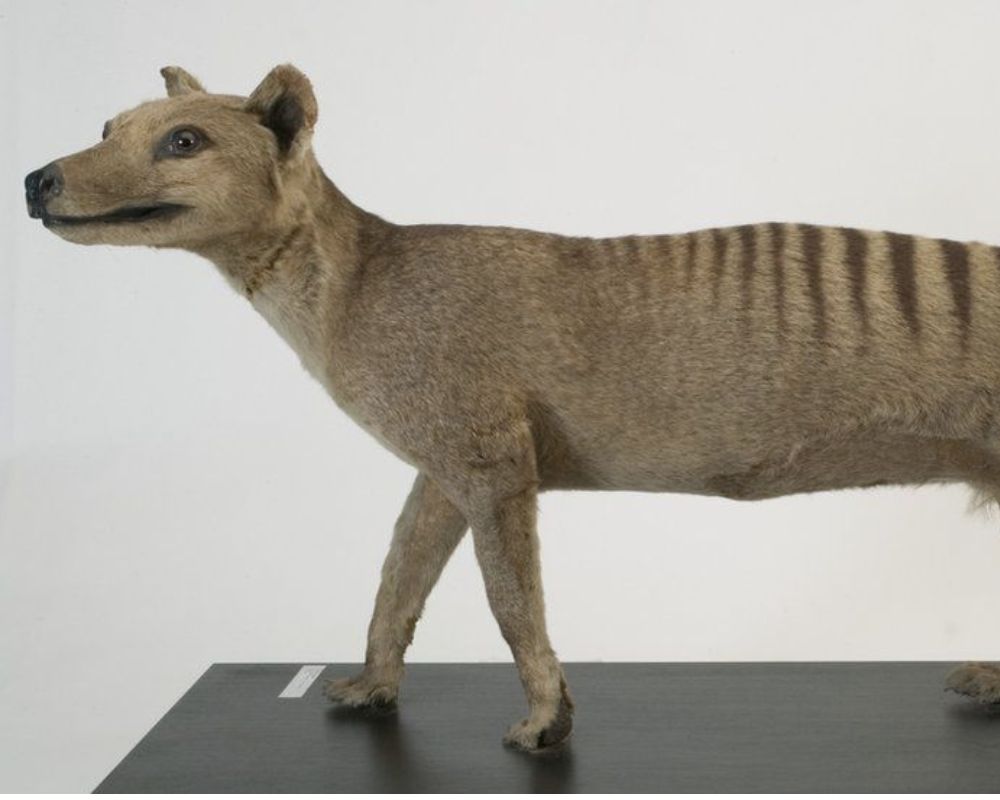

Thylacine, or the Tasmanian Tiger, is one of the most iconic species of Australia. Colossal Biosciences and the University of Melbourne are working together on a ground-breaking attempt to reintroduce the Tasmanian tiger. As per their research, the species of the tiger has been under extinction since the year 1936, and it’ll require a lot of work to bring it back. Russell Wilson, the Wilson Family Trust’s head, started following Pask on YouTube and developed a strong interest in his genome sequencing study. Wilson Family Trust generously donated $5 million to Andrew Pask.

Dr. Andrew Pask

Dr. Andrew Park from The University of Melbourne, conducted the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR). To begin with, Dr. Pask first looked at how intact the genomes of museum specimens were and discovered they were in excellent form, which led him to begin investigating the idea of de-extinction. As a result, in a mouse embryo, Pask revived the activity of a single Tasmanian tiger gene in 2005. No other animal was able to take the thylacine’s position once it disappeared, since it was the only apex predator in the Tasmanian ecosystem. Damaged DNA fragments from museum items and human remains can be assembled and sequenced with incredible precision. They’ve made great advancements in stem cell biology and the capacity to produce creatures from a single cell.

Ben Lamm and George Church

Ben Lamm is the CEO and the Founder of Colossal Biosciences while George Church is the leading geneticist. Both of them are working with Dr. Pasks on the same project. Through gestational technologies and marsupial-focused conservation, they both seek to protect the species. The full-stage artificial wombs that Colossal is developing can aid in entire ex-utero development starting with embryos. For the conservation of marsupials, these gestational technologies alone will be revolutionary.

Saving the Tasmanian Devil

Lamm also stated that by developing an exo-pouch, which will aid in the growth of offspring after birth, marsupial conservation initiatives would also help save the Tasmanian devil from extinction. Twenty to thirty joeys are born to the Tasmanian devil at once, but since the mother can only feed four at a time, only a few of the offspring make it to adulthood. Conservationists working with Tasmanian devils may find the exo-pouch they are constructing for the thylacine project to be of great assistance in taking those additional 20+ joeys and providing them with a place to incubate further.